Nordland Teater (Norway) 2015

Scene 3: The Girl (Hilde Stensland, left) and Woman with Parasol (Jeungsook Yoo right)

Excerpts from reviews:

‘…a performance that surpasses almost anything I’ve ever seen…With wonderfully precise direction and focus on the tiniest of details, Zarrilli has managed to create a truly remarkable experience…an incredibly sensual, beautiful, well-played and rich performance.’ [Armund Grumstad in Klassekampen (Oslo)]

‘…like a deep sea dive into your own soul…[a] truly […] extraordinary experience. After 100 minutes of roaring silence you silently get up from your seat, leave the auditorium slowly, whisper quietly to the person next to you, and realize this is a memory for life.’ Jostein Pedersen in Helgelands Blad (Helgeland)

Director: Phillip Zarrilli

Set Design: Serge von Arx;

Costume Design: Nina von Arx;

Produced by Nortland Teater (Birgitte Strid, Artistic Director)

The Water Station was originally created and performed in Tokyo in 1981 by Ōta Shōgo and his theatre company--Theatre of Transformation (Tenkei Gekijo). The production subsequently toured central Europe and the US in the 1980s. Ōta and his company were searching for a way to turn down the volume or “noise” in our everyday lives in order to be present to the realities of our immediate environment. In that moment of quiet the audience become 'witnesses' to what is before us today in the immediate present...people on the move toward somewhere else.

The Water Station is a non-verbal psychophysical score in nine scenes with incidental music. It has a very simple structure: a series refugees/migrants/travellers are on the move coming from a far distant place, and are continuing on the still longer journey toward some place beyond. Some are individuals traveling alone such as a Girl or the Woman with a Parasol; others are in pairs (Two Men in or Husband and Wife with Baby Carriage); or in a group (The Caravan). These travellers appear on a bridgeway. Just behind the path is a huge heap of discarded ’junk’—objects left by those on this long journey. Once they appear each individual, pair or group encounters and interacts with a constantly running stream of water flowing from a broken water faucet into a pool of water in a catchment area. Each of the travellers encounters the water in their own way. Some observe or encounter another traveler. All eventually continue their journey toward whatever lies beyond. From the audience’s perspective, where these travellers have come from and where they are going we do not know. They eventually pass out of view…heading somewhere.

Hilde Stensland as The Girl, Scene 1.

A young barefoot girl, clutching an old rag-doll appears in dim light along a pathway. She is coming from somewhere unknown, and travelling along this pathway toward… somewhere unknown. Sensing behind her, she stops unexpectedly and looks back toward the place from which she has come. Continuing to clutch her doll close to her, she turns back to the way ‘ahead’ and continues on her journey. Encountering a stream of water running from a broken water faucet into a catchment area, she stops, gazes at the water and cautiously crosses to it. She kneels beside the catchment area, gazing at the running water, and eventually drinks from the faucet. She looks up and out suddenly--something far away has captured her attention—her gaze haunted by something unknown. She senses someone behind her—along the same pathway she has travelled. She looks back…two men appear through the dim light, walking backward, one carrying a suitcase and the other a bedroll—their gazes fixed and intent on what they see in the far distance beyond…that place from which she too has travelled. As they approach she hides herself in a heap of junk behind the pathway.

Jeungsook Yoo as Woman with Parasol, Scene 3.

Scene 4: Husband and Wife with Baby Carriage

According to Ōta, The Water Station is located not in any single specific historical instance of migration due to conflict, but rather ‘anywhere and everywhere, [in] a place out of time.’ One critic described The Water Station as a ‘quiet chamber piece that speaks in the rich language of silence to the neglected part of the soul’. Writing in The Straits Times, Clarissa Oon described the 2004 Singapore production of The Water Station as ‘…a wordless…tone poem whose silent chords struck notes of exile, loss and fraying endurance…’

With its slowed down everyday movement, this non-verbal performance lasts 105 minutes creates a completely different experience for an audience from narratively driven, text-based theatre. In his theatre aesthetic, Ōta developed a process of ‘divestiture’--discarding or paring away of anything unnecessary including spoken language so that actors and audience alike are taken out of their everyday world in order to focus on the irreducible elements of our shared human existence—what Ōta calls “the ‘unparaphrasable realm of experience”. The script for The Water Station is a sparse 20 page document—a simple record of the basic staging and images Ōta and his company devised from a diverse set of source materials. Although this is a non-verbal performance, as Ōta explains, “there are words here…you simply can’t hear them.”

The main premises guiding both the original Japanese production as well as our new production are “acting in silence” and “acting at a very slow tempo.” In the performance, everyday actions are slowed down. Acting “in silence” and at “a slow tempo” make special requirements on the actors. In order to slow down the actors, and allow them to be more attentive to their environment, each other, and each action they perform, as the director of the production I have taken the actors through an initial two week workshop (in May, 2015), and extensive and on-going daily training of approximately 75 minutes prior to our rehearsals. This training heightens the actor’s sensory awareness through yoga, the Indian martial art (kalarippayattu) and the Chinese martial art (taiqiquan). All three disciplines focus on at first being attentive to the breath, and then to the breath as it ‘moves’ us and opens our awareness. This type of awareness training is essential to prepare the actors to inhabit Ōta’s aesthetic of ‘quietude’ and to divest themselves of anything unnecessary in the moment of performance. It is also essential in helping create a sense of ensemble and shared process.

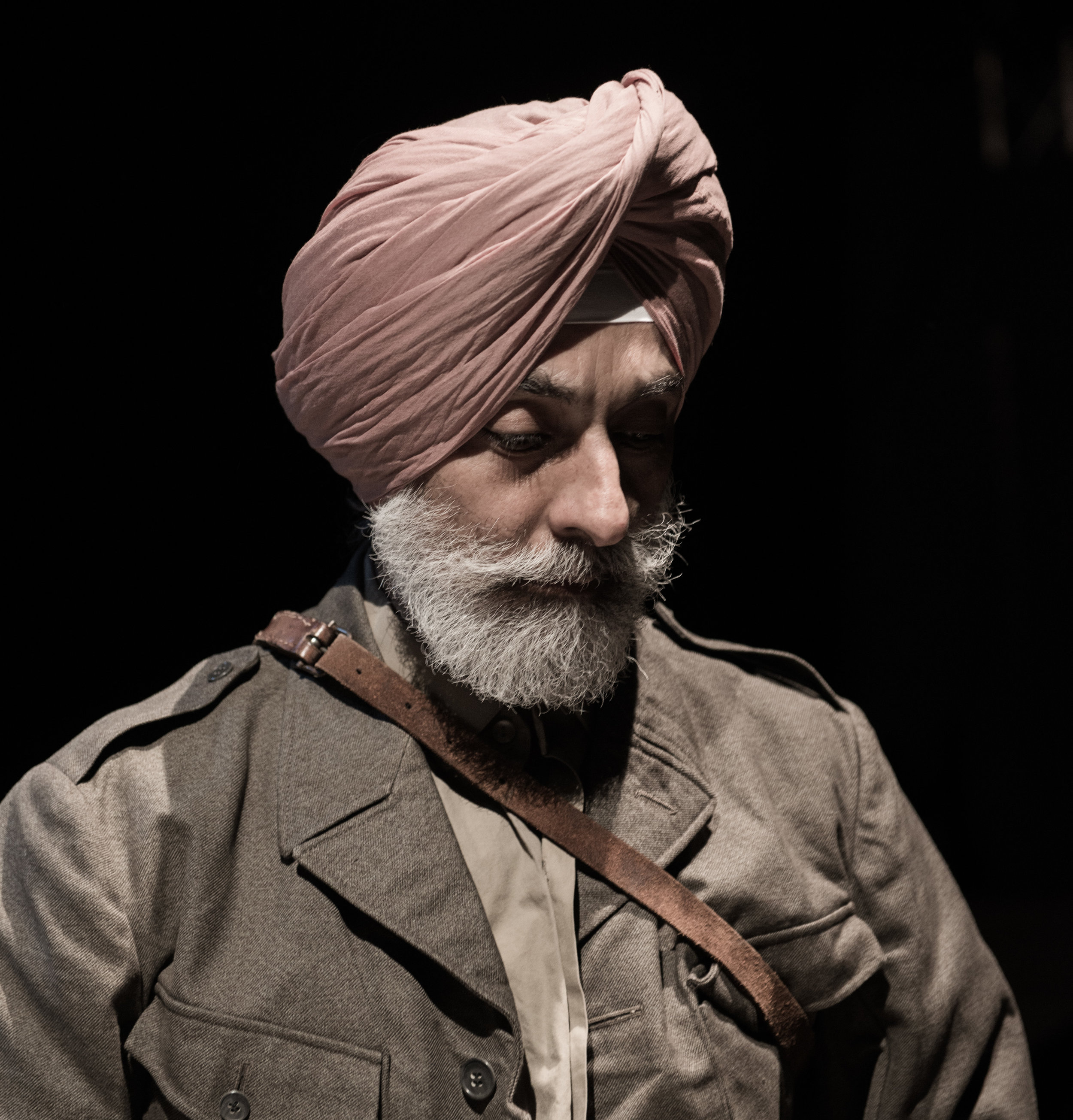

Navtej Johar in Scene 6: The Caravan

Photographs: på Ketil Born

FULL REVIEWS

‘Time is a relative concept’

Physical and detailed theater conveyed in a tempo that provides plenty oftime for contemplation

Amanda Grimstad (published in the daily newspaper Klassekampen 28 Sept 2015)

The Water Station by the Japanese playwright Ota Shogo (1939-2006) is a theatrical production very unlike what we’re used to seeing. Ota was one of Japan’s foremost playwrights and he developed a theatrical language stripped down to the bone, and also slowed down both volume and tempo. The Water Station from 1981 is a great example of this. The piece is in essence created on two basic principles. In the performance not a word is spoken, and everything happens at an unusually slow pace. Shogo takes us to a post-apocalyptic world, situated around an outdoor water faucet where we meet many different people--mostly very vulnerable and stripped down. With its slow-moving pace, every detail becomes mercilessly visible.

The artistic director at Nordland Teater, Birgitte Strid, saw a production The Water Station in Singapore in 2004, and immediately wanted to produce it in Norway; however, she found no home for it. When she became the head of the theater in Nordland, and had far greater means to do as she pleased, she asked Wales-based actor and director Phillip Zarrilli--who also directed the Singapore production--to come to Nordland Teater to direct it once more. With him he brought three actors from Korea, Singapore, and India who all know his theatrical language. Along with a very international group, and three from Nordland Teater’s own ensemble, they were ready to give us a Scandinavian premiere last Thursday. The result was a performance that surpasses almost anything I’ve ever seen.

We’re somewhere in the middle of nowhere where people come and go, they meet and they stop at the water station. No one says a word, but we still understand who they are, what they’re doing and why they’re there. Serge von Arx, has created a very functional set design, that will also work on tour. A raised wooden walkway leads to and past a water station. The sound of running water is the only thing we hear until music by Satie and Albinoni Satie, among others, break the silence. Behind the water station is a mound of garbage--things left behind by the travelers. That’s all.

Ivar Furre and Navtej Johar as Man 1 and Man 2 with The Girl in the junk heap. Scene 2.

In this somewhat dark and solemn set design, juxtaposed by the life-affirming water, we’re shown nine vignettes with incredibly seamless transitions. Fifteen characters are played by ten actors, and we begin and end with the same scene. Slowly, very slowly, step-by-step, Hilde Stensland walks toward the water station--a young girl clinging to her doll. In these opening moments she creates a contract of sorts with the audience about tempo and dramaturgy, and through her excellent and expressive acting she sets the standard for the whole production--a very clear and relatable language where a slight movement in a hand or the faintest hint of something going on in the face speaks volumes far greater than long monologues. We accept these terms, lean back in our seats and allow time to shift into a different mode. Because in this universe even time is relative and when we go to black nearly two hours later it feels like barely an hour has passed.

The script for this piece is only twenty pages of simple stage directions, music choices and such. And yet, it becomes a performance extremely rich in detail and full of possible interpretations. When the show was initially performed in Japan in 1981, it was probably easy to make a connection to the atomic bombs which fell 70 years ago, when words became useless and void of meaning.

In this production at Nordland Teater we’re seeing a more universal interpretation focusing on the loss of language and apathy created by all catastrophes. But we can also see many other interpretations. In a performance where every detail becomes so important, we end up sitting there looking for metaphors, and find them all the time--maybe even where there really are none. But that is just what humans do.

With wonderfully precise direction and focus on the tiniest of details, Zarrilli has managed to create a truly remarkable experience. And although we should all be allowed our individual interpretations, for me there are two very obvious and current themes at play here.

This is a piece about migration, people fleeing and dragging with them their stories, but on the way they must leave more and more of it behind; hence, the heap of junk behind the water station. The pressing refugee situation in Europe, and the laws that regulate this situation becomes very poignant. And secondly there’s the environmental issue between this catastrophe being alluded to and the life in the running water, the connecting point, the hope. That is where these people drink, wash, even bathe.

The Water Station is an incredibly sensual, beautiful, well-played and rich performance. Nordland Teater should be incredibly proud of their bravery in putting on such a daring production, with such high artistic ambition. And they’ve succeeded in every way.

Scene 7: Husband (Stein and Wife (Jing Hong Okorn-Kuo)

Quietude: Seeing The Water Station in Sandnessjøen, in the middle of Helgeland county surrounded by water, the water of life, is like a deep sea dive into your own soul.

A memory for life.

Jostein Pedersen Helgelands Blad 02. October 2015 (name of paper/date)

· Nordland Teater: The Water Station by Ota Shogo (1939-2006)

· Kulturbadet, Sandnessjøen Wednesday

· Director: Phillip Zarrilli

· Set design: Serge von Arx

· Cast: Ten actors from five countries, no dialogue

COMPLETE SILENCE. This is truly an extraordinary experience. After 100 minutes of roaring silence you silently get up from your seat, leave the auditorium slowly, whisper quietly to the person next to you, and realize this is a memory for life.

The roaring silence is because of the water station, a running faucet into a small well, next to a pool. There’s no dialogue, but ten actors portraying characters meeting at a water station. It is the water of life. They’re fleeing something. Only the gods know towards what.

At the water station is a collection of earthly goods – suitcases, boxes, bags. Things left behind. You can’t take it with you when you leave. In our human way, they all carry something with them, something to hold on to, something they feel like they need in order to exist. The girl and her doll. The old lady carrying her whole life in a basket on her back, the girls playing with the precious water, the men and their suitcases, the loving couple and their baby carriage. The dearest thing they own. They’re thirsty.

SLOWLY. They move slowly. That means very, very slowly. But how slowly is slowly, and how fast is fast? The faces all appear clean and free of make up. There’s minimal mimicry, as if to open up and welcoming us to inhabit the untouched. But they are moving. Slowly, slowly. The muscular performance is demanding and precise, the limbs in some sort of absurd harmony telling these wordless stories. Yes, certainly, this is yoga for the soul. Time. And space.

Breath. We breathe together, don’t we? Yes, there are forces at play. There’s will. They’ve found the water station. The water of life.

And that is where, in their faces; we, 120 souls, in a dark auditorium a Wednesday evening in Sandnessjøen find ourselves. Or a sister or a brother. We’re searching for dislikes, and likes – and there! – there I am. Breathe in. Breathe out. Is this the way things are? Yes, that’s how it is.

Running water. Roaring silence. One hundred minutes of meditation. It felt so good.

Scene 4 into Scene 5: Old Woman with Basket on her back (Jing Hong Okorn-Kuo) approaches Husband and Wife by the water station.

PREJUDICE. Honestly speaking I can say I was one of those who found it comical that Nordland Teater’s first performance at the opening of the Kulturbadet would be a piece of Japanese contemporary drama without dialogue, and a small UN on stage. All my prejudice was at play: traditional kabuki in white face, impractical costumes, samurai-glorification, honor ideology from a thousand year worshipping through religion and emperor power, hara-kiri, cynical j-pop, martial arts, and a faint hope of intellectual refill from the authorship of Yukio Mishima and Haruki Murakami. I was certainly wrong about all of that. And I’m so happy about that.

Although I’m sure Kulturbadet, in a moment of weakness, would have wanted a flashy musical for the opening, where the line was out the door and down to Petter Dass’ Square. To that I would argue that in The Water Station and its 100 minutes of roaring silence, there’s more going on than in Les Miserables, Mary Poppins, and Jesus Christ Superstar all put together.

This play first premiered in 1981, where it was called a piece of “living silence” where the objective was to turn down or switch off the roar of daily life, and look into the depths of silence. Today this comes across as a fist slammed into our consciousness in regards to the current refugee crisis, and Nordland Teater is using that connection as much as they can. The piece also has clear associations to the war, especially Hiroshima, especially due to Shogo’s own background as a Japanese refugee in China during the war. This truly is silence making a tremendous amount of noise.

BRAVE. The Artistic Director at Nordland Teater, Birgitte Strid, is not only a brilliant director, she’s also a very brave artistic director. She saw this piece in Singapore in 2004 and couldn’t forget it. When she came home she tried getting Norwegian theatres to produce it – they all turned her down. When she became Artistic Director, she acknowledged that if the piece was to be produced here, it had to be directed by the same man who did the Singapore production. And that’s what happened; he had only one condition, that he could bring three actors who knew the piece very well.

And then they came here, alongside others, three of which are permanent members of the Nordland Teater ensemble. I am convinced that theater has the power to transform lives. I am also convinced that theater truly depends on time and place. Seeing The Water Station in Sandnessjøen, in the middle of Helgeland county, surrounded by water, the water of life, is like a deep sea dive into your own soul. We are scarred from the. We always open our doors for people fleeing their homes. We know that silence is frightfully loud. We are thirsty by the water station. Thank you.

A COMPLETE VIDEO OF THE WATER STATION IS AVAILABLE FOR PRIVATE VIEWING BY PRODUCERS.

CONTACT PHILLIP ZARRILLI FOR THE URL AND PASSWORD.

Devastation and collapse...