Gitanjali Kolanad dancing with the second of three puppets that 'de-materilize' in Walking Naked.

Having trained in kathakali dance-drama and in kalarippayattu, the martial art of Kerala, India that has been utilized by so many Indian dancers as a part of their training, Phillip Zarrilli has a long history of collaborating with dancers/choreographers from South Asia, especially bharatanatyam dancer/choreogaphers Gitanjali Kolanad (Chennai, India/Toronto, Canada) and Stella Subbian and Mira Gokul of SANKALPAM (UK).

COLLABORATIONS WITH GITANJALI KOLANAD

WALKING NAKED (1998-2006)

Walking Naked premiered at the Museum Theatre, Chennai in 1998 and then toured internationally between 1998 and 2006. Walking Naked by the 12th century radical renunciant and poet/saint/devotee of Siva, Mahadeviakka. Zarrilli and Kolanad co-created this radically experimental solo dance-theatre performance using and responding to Mahadevi’s ecstatic poetry which focuses on the dematerialization of the body. As a mark of her devotion, she both left her marriage and chose to walk naked the itinerant path of sainthood. To capture the essence and power of Mahadevi’s story of radical female devotion, we commissioned three different designers to design and make three distinctive puppets, each of which would ‘de-materialize’ in its own way: (1) a rod-puppet cast from ice that began to melt onstage during the performance, (2) an upper-body cloth puppet that Gitanjali ‘wore’ and from which she was able to extact lines of Mahadevi’s ecstatic poetry printed in Kannada from inside various centres of the subtle-body of yoga, and (3) a huge larger-than-life brass-wire ‘see-through’ folk-style puppet which Gitanjali ‘put on’ after its face was revealed when fire-paper was burned off its face. This unique solo dance-theatre performance combined text, puppetry, and both traditional and new ways of using bharatanatyam choreography.

First production

1998

Museum Theatre

Chennai, India

1998-2006

Toured to:

Mumbai, Glasgow, Toronto, Seoul, Madison, New York

Director Phillip B. Zarrilli

Choreographer & Dancer Gitanjali Kolonad

Music composed by Babu Parameswharan

Review ESSAY in Puppetry International (Fall/Winter, 2005) WALKING NAKED

The story of Mahadeviakka told through dance and puppetry

Matthew Cohen, PH.D., and Rolande Duprey

Based on interviews with Gita Kolanad and Phillip ZarRilli in 2003 and in 2005

Walking Naked is a piece of story-theatre with puppets and dance, based upon the life and poetry of the saint-poet Mahadeviakka. It was devised by Indian-Canadian dancer Gitanjali Kolanad and American director and actor trainer Phillip Zarrilli, drawing extensively upon a number of South Asian performance practices, principally Bharatanatyam, as well as experimental theatre techniques. The music and recorded vocals are by Babu Parameshwaran, a Madras composer, now living in Los Angeles. This solo piece has been performed all over the worldfrom Asia (Korea, Singapore, India) to the U.K., to the U.S. and Canada.

Beginnings

The beginnings of Walking Naked can be traced to a chance encounter by Phillip Zarrilli, who was then a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Gitanjali Kolanad, a professional dancer then living in Singapore, at a Theatre in Education conference in Brisbane, Australia.

Kolanad is a dancer, choreographer and director, as well as the author of a travel guide, Culture Shock!: India (1st printing 1994). She was born in India (in Kerala), and moved to Canada as a child, where she studied piano, ballet and modern dance.

In 1970, when Kolanad was 16, she ran away from home. When I left home my parents realized that the situation was very desperate and they said, "Fine you don't have to go to high school. How about going and spending a year in India?" And that was more tempting. I had a couple of months of living on the streets in Toronto and it was starting to be winter so I thought, "Oh, well that sounds like a way to save face." You know, I didn't have to come back home. So off I went to India.

Kolanad enrolled in Kalakshetra to study Bharatanatyam. Bharatanatyam is a new interpretation of traditional temple dance that in the past was performed exclusively by hereditary sacred dancers or devadasis.

In 1989, Kolanad moved to Singapore with her (second) husband, a German radio journalist. Living in Singapore, which is 2.5 hours from Madras by plane, allowed her to spend all her holidays in India. She choreographed large-scale work for the Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society, a school for the arts (founded 1949), and studied with the school's Sinhalese teacher of Bharatanaryam, Shanta Ponnudurai. (By chance, both Kolanad and Shanta Ponnudurai now live in Toronto and continue to collaborate.)

During the 1990s, she occasionally performed classical programs, but increasingly focused on her own choreography and dance-theatre.

Her new pieces during this period included an adaptation of Bertolt Brecht's The Seven Deadly Sins for three dancers, one actor, dummy horse dancing and video that she adapted, choreographed and directed. This piece, commissioned by the Max Muller Institute in Madras, used both Bharatanaryam and film dance vocabulary and was considered quite radical by established standards of Bharatanatyam.

She also collaborated with a Singapore-based American video and performance artist, Ray Langenbach. They created new dance, theatre and installation work dealing with censorship, the construction of gender and homosexuality.

In 1998, she returned to Canada with her husband, settled in Toronto and embarked on a series of collaborations with a Canadian violinist.

Kolanad met Zarrilli shortly before her return to Canada, at an international theatre educators conference in Brisbane, Australia around 1992 or 1993. Kolanad knew Zarrilli principally as a scholar, from his first book on the South Indian theatrical tradition of Kathakali, The Kathakali Complex (1990). Both Kolanad and Zarrilli had also trained in the Kerala martial art of kalaripayattu, which is the pre-expressive basis of Kathakali as well as a rigorous and precise discipline in its own right. Kolanad had studied kalari while living in Delhi, and Zarrilli had been studying and writing about kalari since the 1970s.

What Kolanad appeared not to know about Zarrilli was that in addition to being a theatre scholar, he is also a theatre practitioner and actor trainer. Much of his work is based on psychophysical acting techniques, a hybrid of tai chi, kalaripayattu and other Asian expressive and pre-expressive traditions, with his own devices and Western theatre heritage. Zarrilli and Kolanad spoke tentatively at the Australia conference about the idea of collaborating. Subsequently, Zarrilli obtained a Creative Artist Award from the University of Wisconsin to develop new artistic work. This supported expenses for production and travel for what eventually became Walking Naked.

Zarrilli traveled to Singapore to do some exploratory discussion and decided that they could actually work together. The collaboration continued, spanning three continents. Kolanad traveled to Madison to work with Zanilli at his home university and then later went to Wales to continue the process. (Zarrilli had since moved to the U.K. and was a professor at the University of Surrey.) Final rehearsals were in Madras.

It was Kolanad's idea to create a piece dealing with the life and poetry of the 12. c. Karnataka poet-saint Mahadeviyakka. Mahadevi, whose short poems or vacanas in Kannada free verse, are exquisite jewels of oral tradition. Vacanas literally means "saying, things done." These sayings were only written down posthumously. Some 200 years after her death, a biography of sorts was compiled. This biography, known as the Sunyasampadane, is a hagiographic text that collates the sayings and poetry attributed to Mahadevi with a telling of the story of Mahadevi's life.

Sometimes referred to simply as Akka (which means "older sister"), the poet was said to have run away from her arranged marriage in order to remain a devotee of Siva, whom she called Cenna Mallikarjuna. She was discovered "walking naked" by a community of Siva devotees, who questioned her commitment. When asked by Allama, the saint, why she was naked, she replied enigmatically, "unless the fruit inside is ripe / the outer peel won't lose its shine" (from the A.K. Ramanujan translation).

For bhakti devotees of Siva, like Mahadevi, "Siva is perpetually immanent in the individual as the soul of the soul, but yet is other than souls in his transcendence." Mahadevi's quest to fully know Siva thus simultaneously (and rather paradoxically) involves self-knowledge and self-transcendence.

Kolanad had been thinking about doing a piece based upon Mahadevi's poetry and life for many years, since reading the poems collected by Ramanujan in Speaking of Siva.

She's so incredible, such a romantic personality. She died very young. She was this woman in a male-dominated world. I imagine her to be something of a superstar [...] to have that kind of almost rock superstar personalim.

Kolanad had been interested in creating a piece about Mahadevi for years but had been unable "to find the right way" to perform it. A simple use of abhinaya, the highly codified symbolic language of expression of Bharatanatyam, would make it "banal."

I wasn't finding the way to work with it until I met Phillip and then Phillip created this beautiful structure, all the puppets, the images of disillusion. I don't have to pretend anything really. The puppets are Mahadevi and I'm just there letting them show what's happening to them. [...] Everything theatrical about this performance is Phillip's.

The text she used was an as-yet-unpublished manuscript translation by Judith Kroll of the Sunyasampadane. Kroll was a good friend who lived in Delhi at the same time that Kolanad was living there. Kolanad presented the materials she had collected from Kroll and others to Zarrilli. Zarrilli stated:

I found the material quite interesting. [...] It's a pretty remarkable story of this figure. She's a pretty radical figure of the 12th century-the way she makes all the choices that she makes. [...] In my reading of the materials, clearly this was revolving around the body and dematerialization of the body in some way. So how could we work with this with Gita's dance?

Zarrilli and Kolanad made the choice to present the text in English, "because people who go to dance performances, even in Madras, speak English [. . . ] and Gita wanted the challenge of working with text." There was a lot of time in developing the score, the script, sitting at the computer, getting up, trying some choreography, semi-devising. Kolanad was thinking choreographically around certain images and a set of performing objects. "We thought it was important that [Mahadevi] become manifest through the performance," said Zarrilli. "If Gita was just paying attention to technique and choreography, the figure could become very secondary to the choreogaphy and here we were trying to keep some balance."

Gitanjali Kolanad dances with the brass-wire folk-style puppet.

The Puppetry:

It was Zarrilli's idea to use puppets.

The world-view in her poetry is so much about transformation. After discussion on how to represent this, we decided upon using puppets. Each of the three puppets represent a different poetic phase of her life. We were doing a kind of life story, so we selected key poems as aspects of her biography.

There were four performing objects present in the piece, three puppets and one spear.

The spear dance was in response to a very specific argument Akka Mahadevi had with Allama, a leader of the Virasaiva community. The poem speaks of one-pointedness "The guru gave a spear called linga into the hands of one fully concentrated." She becomes one-pointed, as a spear, after the argument with Allama.

The question was, "How do affect a state of consciousness where you are one-pointed?" The text itself was extremely war-like:

I fight, I win

A man called Kama (desire) Krodha (anger) and others

Were defeated and ran away

Since the spear was very deep inside me and vanished...

They decided upon using a literal spear. Gita begins the sequence by balancing it on her head, (there are many folk traditions of balancing things on your head such as Teyyam, Kavadi). Soon the spear it self becomes a partner in the dance, moving with and by Gita as she twirls around the floor, playfully rolling it around her body.

Each of the three puppets used had "points of departure" (PZ) from Asian traditions of performance, though no real attempt was made to copy something. They were used to represent ideas of dematerialization, a theme also present in the texts. The first puppet presented in the 50-minute piece is a small rod puppet whose body is made of ice, and melts over the course of the show.

The rod puppet cast of ice that begins to melt during the performance.

In order to develop the movement criteria for the second puppet (out of cloth), GK went to Japan while working on Walking Naked and watched a lot of bunraku. "I tried to get the feeling [with the cloth puppet] where the other person is on stage but it is the puppet who is really alive which is what you have in bunraku. You see the puppeteer the whole time but you have the sense that they're not important, that they've infused every bit of their life into the puppet. I tried to get that same sense of putting everything into the puppet."

Eventually, she succeeded: "The cloth puppet would take over, I would feel as though I disappeared and the puppet would come to life; with the other puppets, it was more about me making them come alive..." The cloth puppet, operated directly from behind, has texts pulled out of the chakras of the body.

The third and last puppet presented in the piece is covered exquisitely with paper that is set on fire, revealing a brass skeleton. Kolanad then crawls into it, balancing it on her shoulders as she dances. This shape was specifically influenced by Teyyam, which was important choreographically for Kolanad as a point of inspiration. It wasn't necessary for me to go back and incorporate any exact traditional art. It wouldn't be right. I could use them as a subliminal memory.

The poetry spoke of "The God of desire burnt to ash" ... For some Indian women, in a feminist reading, it could be the story of molestation. Indian audiences questioned this part - How could it be beautiful? But for Akka Mahadevi, it was about the transformative experience - not a molestation, but a positive change.

In coaching Gita Kolanad for the work with puppets, Zarilli asked Kolanad to extend her energy into the objects. As in weapons work (in Kalari), the weapon is used to extend the energy of the warrior. Kolanad has had some Kalari training, though no weapons work. This particular aspect took a while for her to incorporate into the performance. "It's not the movement but the quality of the movement, which comes from being centered and focused, which is what kalarippayattu teaches you..."

Performing with puppets requires the performer to sublimate his/her ego in order that the puppet may be fully realized as a character.

The brass puppet I needed to invest everything in .... It was very topheavy, being balanced on my shoulders, it was about the shift of weight. I had to let the movements happen without losing control.

If she moved too far in one direction it would topple, so she had to play a double balancing act: the puppet as well as getting as much movement out of it as possible within the limited range.

The puppets, therefore, were challenges on numerous levels. Kolanad found the ice puppet to be very restrictive, but the others were more accessible, since they were connected directly to her body: " They take on a life of their own. The nature of each puppet demands a certain kind of movement."

The "South Asianess" of Walking Naked

Mahadevi herself wrestled with the problem of the communication of rendering her own sense of Shiva. This sense was "the Experience" or anubhava, "an unmediated, immediate, and unpredictable experience." Thom Brooks, in a recent article on Mahadevi comments that "Certain kinds of knowledge may only be transferred via experience, with knowledge of Siva's divine presence being but one example of this. In this light, Mahadevi chooses well in using vacanas in the effort to share with us the object of her experience. Through the use of prose she may employ various metaphors and perspectives to make her point. Indeed, poetry uniquely gives her the opportunity to attempt to cross the impossibility of sharing knowledge she has gained via her subjective experiences with those who have not had the same experiences."

Walking Naked reinforces this experiential knowledge through theatre's unique capacity to engage spectators in a variety of semiotic channels. The puppet made of ice that melts continuously throughout the play, the cloth puppet, the spear, and the puppet set on fire are all powerful signs that are universally recognized. But, there are certain other signs within the piece that are specific to India and Indian belief systems. Someone who doesn't know South Asia won't see some of the subtleties in the piece" says Zarilli:

... including the chakras that are part of the wire puppet design, or the Kanada text that is pulled out. The triangle design that is marked on the floor surrounding the performance area is a tantric design-the vagina of the world. All the imagery has a unity to it in the Shaivite Siva-Shakti realm. All of that's there and it's available if anyone knows it. A lot of people in the West will just look at it and it will just be maybe, maybe an interesting design and interesting objects. Hopefully, though, they'll get something from the text and the dance that suggests some of the elements that have more resonance to people with more knowledge.

Ralande Duprey is a frequent contrubuter to PI. She has her MFA in puppetry from UConn.

Dr. Matthew Cohen is Lecturer in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies at the University of Glasgow, UK

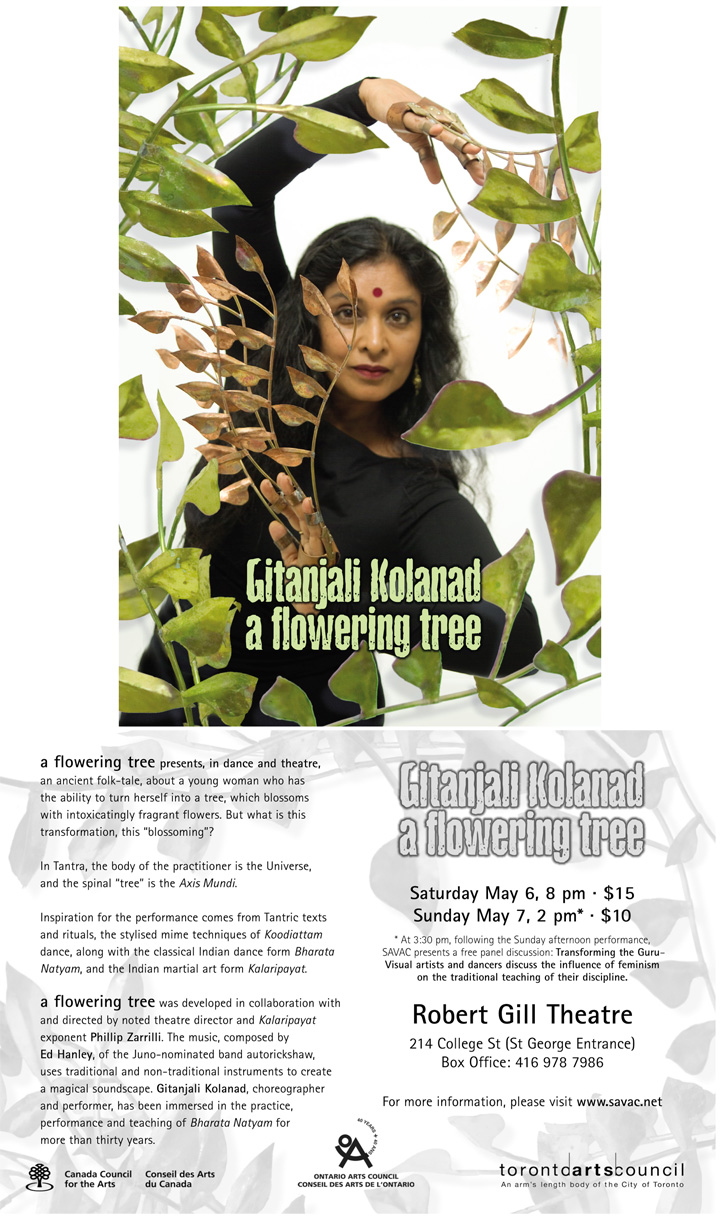

THE FLOWERING TREE: Co-created by Gitanjali Kolanad and Phillip Zarrilli (2006-2008)

A Flowering Tree presents, in dance and theatre, an ancient Kannada folk-tale about a young woman who has the ability to turn herself into a tree, which blossoms with intoxicatingly flowers. But what is this transformation, this "blossoming"? In tantra, the body of the practitioner is a Universe, and the spinal "tree" is the Axis Mundi. Inspiration for the performance comes from the Tantric texts and rituals, the stylised techniques of transforming from one ‘character’ into another that is an integral part of the ancient Sanskrit kutiyattam dance-theatre of Kerala, along with the classical Indian dance form bharatanatyam, and the Kerala martial art, kalarippayattu.

First production

2006

Robert Gill Theatre

Toronto, Canada

Director Phillip B. Zarrilli

Music composed by Ed Hanley

Choreographer and Performer Gitanjali Kolanad